PCjs Machines

Home of the original IBM PC emulator for browsers.

PCjs Blog

Introducing Programmable Calculator JS

For years, we all assumed that PCjs meant “Personal Computers in JavaScript.” Even I thought that. But now it turns out that it also stands for “Programmable Calculators in JavaScript.” Who knew?

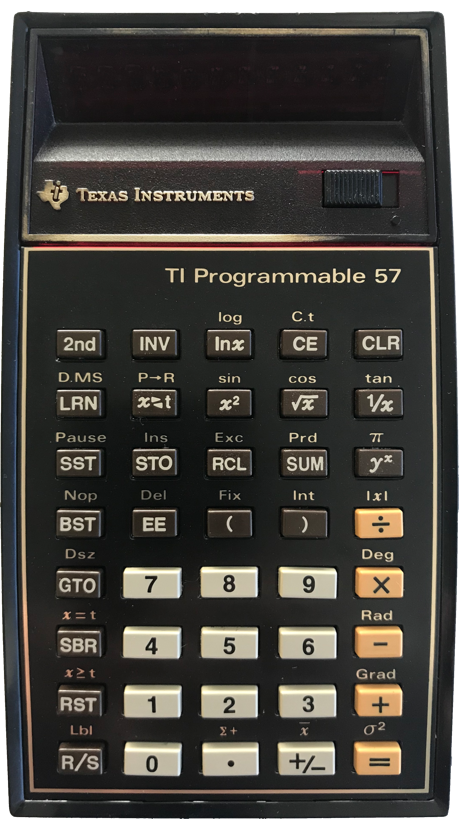

That seems only appropriate, since my very first programmable device was a TI-57 Programmable Calculator. Or more precisely,

an EC-4000, which was Radio Shack’s version of the TI-57. Pictures of my EC-4000 are below. I have a hunch that if I peeled

off the Radio Shack sticker on the back (underneath my custom Dymo label), it would say Texas Instruments electronic calculator.

The EC-4000’s rechargeable battery was long dead, but it was easy enough to follow Dr. Monk’s Advice and “convert” the calculator to use a 9V battery.

Unfortunately, while my EC-4000 powered up, a few of the buttons (like 0) didn’t respond, and I wanted to have an operational

TI-57 before taking my own apart, so I picked one up on eBay, too.

The TI-57 was a great device and I wrote all sorts of programs for it, although my fascination with it was quickly superseded by the Challenger 1P I got later that year.

I didn’t get very far fixing the unresponsive buttons on my EC-4000, because I began wondering how hard it would be to write a TI-57 emulator. It was no real surprise that several other people already had the same idea, but as far as I could tell, only one person, who goes by the name “HrastProgrammer”, had gone all-out and created a simulation of the TI-57 calculator chip, the TMS-1500: basically, a very simple CPU with 20+ registers, along with 2K of ROM and assorted circuitry for driving the LED display and scanning the keyboard.

This was an interesting challenge, because while no system manuals had ever been published for this “single-chip

computer”, it was documented in excruciating detail in at least nine TI-57 Patents.

And excruciating is the right word, because only a hard-core chip designer would love reading the many delightful

pages of how OR gate 515 is responsive to the DISP and REL HOLD signals or how NAND gate 468 is responsive to the MSKΦ

signal from gates 220 received via inverter 434.

HrastProgrammer’s work was a great step forward, proving that an emulator was possible, and other people used it to learn more about TI-57 internals. For example, Claus Buchholz wrote a few articles (“The TI-57 Memory Map” and “TI-57 Constant ROM”) with the assistance of that emulator.

Sadly, HrastProgrammer’s work is closed-source, so many of the details that he gleaned from the patents and learned along the way remain buried. His FAQ summarizes his opinion of open-source projects:

Yes, what about it? From time to time, I receive a request to release them as open-source.

Sometimes it sounds like I SHOULD DO THIS because it is to be expected. Well, I SHOULD do

only what I WANT to do. And I DON'T WANT to release anything as open-source because I have

no reason to do this. Except in a few rare cases, I don't like this open-source concept at all

so I will not participate. All my emulators will be closed-source forever. Don't waste your

and my time asking such questions.

We know from a handful of blog posts that HrastProgrammer originally decided to use a hand-edited version of the TI-57 ROM, extracted from six TI patents, and that he probably made a number of useful corrections and discoveries along the way. However, in the most recent version of his TI-57E emulator, he uses an electronic dump of a production TI-57 ROM, reportedly obtained from a friend and which he said he could not distribute.

UPDATE: With a Windows debugger and lots of patience, I was able to isolate and extract the electronic ROM dump stored inside HrastProgrammer’s TI57E.EXE binary. See the TI-57 ROM page for details.

My only choice was to go down the same road that HrastProgrammer travelled and pore over the same TI patents. They are definitely valuable historical documents, filled with detailed diagrams, instruction decoding tables, and object code listings of the chip’s entire 2K ROM. Unfortunately, as several people before me had found, the ROM listings in nearly every one of the nine patents were all slightly different, no doubt because they had all been typed by hand (with one possible exception). Given all the obvious errors (invalid digits, excessive digits, and missing digits), it was all but certain that the listings also contained numerous non-obvious errors.

One enterprising person, Sean Riddle, had carefully scrutinized the ROM circuits of a Decapped TMS-1500 Chip and created a “transcript” of all the ROM bits. To get some idea of how tedious that process is, here’s a small section of that ROM image:

So, how to be sure that that transcript was accurate? I decided to make my own independent transcript of all 26,624 ones and zeros, and then compare the results:

1011011010110101-1111100100011011-1001101011110101-0000000000101001-0101111101001010-0110010100011110-0011011111011001-1000000000111010-0001010000110001-1000010100100101-0101111001111011-0101111111110110-1000000100010000

0100101001111010-0000001001110101-0110101101010110-0000100001111000-0010000000100001-1111111100001011-0001001011010000-1011000001011010-1001101011101111-0110100110110000-0111111111000111-0101010110110010-1010101000101101

0100111101010001-1110111001011011-0101100011111110-1110011101011010-1001101110001100-0001010101111101-1010001110011011-0001110100010011-1100000011011111-1111001110000111-0001101101110000-1100011111111110-1100000010011011

1111110101010011-0010011010011111-0000111000000010-1101011010011001-0000000111101101-0011111000100100-0000000100100000-0100000000011001-1001100000000010-0100000001010011-0110001111101101-1011111001111011-1011100110000000

0010010110010000-1001111100011001-1100101010110000-1101101001011011-0001000100011101-0001101000011101-0010000110010001-1010001000010001-0000001000110010-0110001111100100-1101100100101011-1111111111111101-0100001001110110

0110011011110111-0100011000101000-0011010101101101-1011011000000101-0011000001001110-1001001000011100-0010100000001000-1001011000110100-0100001011101111-0110010111100010-0101111111000000-1001100010111101-1010010001101001

1011110111111110-0100111101111010-1000010001111100-1000101000111110-1110110101110111-0001101010000011-0110000100010000-0010001000001101-0001101001110000-0011000111010101-1100100110000111-1110101111111110-1001101001110100

0110010010001111-0101111110101100-1100111110010001-1010011111001001-1101010110111100-1101011000011111-1000000100101000-1101000000000011-1000110010011101-0011100100100000-1011011111111010-1101011100001010-1110101100001001

....

As my TI-57 ROM page explains, I found 4 bits that differed. I passed the corrections on to Sean, and then decided to go with this new transcribed ROM as the basis for my own emulator.

What you see below is the current state of the PCjs TI-57 emulator. Just today, I finished “wiring” up the LED and Keyboard devices to the TMS-1500 Chip device, and so far, basic arithmetic operations look good. I’ve not exercised it much beyond that, because I’m not ready to go down more debugging rabbit holes just yet. But if it does crash, there’s a handy “Diagnostics” window attached to it that should display useful information about what went wrong, and it even includes a “mini-debugger”.

With the PCjs TI-57 emulator, I also decided to take a fresh approach. Instead of using the same old ES5-based PCjs shared modules, the TI-57 emulator is built with a new set of ES6-based Machine library modules, including:

Since I’m not currently “compiling/transpiling” any of that code to ES5 (as I’ve done with every other PCjs machine to date), you have to be running a modern web browser. I’ll probably add an ES5 fall-back mechanism eventually, but for now, it’s rather refreshing to be using modern JavaScript language features and not constantly worrying about backward-compatibility.

Debugger

Jeff Parsons

Nov 5, 2017